I was delighted to be invited to speak at a conference commemorating the six hundredth anniversary of the cathedral of San Martino in Lucca. I was supposed to go out and present in person, but unfortunately had to present online due to COVID. I was surprised to be asked to present in English, but I wasn’t the only one, so I suppose it was to mean that there would be more of a mix of Italian and English. The proceedings were published recently in the beautifully-covered volume entitles All’ombra di San Martino: Arte, storia, devozione (In the Shadow of San Martino: Art, History, and Devotion).

My chapter was on The Bianchi of 1399 at Lucca: Navigating a Medieval Popular Religious Revival. Lucca was one of the case study towns for my PhD, and so it was fun to be able to write solely about it for this piece. Essentially I was writing about the ways that Lucca is and is not representative of the Bianchi of 1399 as a whole.

For those who are new here, the Bianchi of 1399 was a popular religious revival in response to an epidemic of plague. The people of northern and central Italy donned white clothing and processed for nine days, either from town to town or around their hometown. Lucca was a real hub of Bianchi activity, receeving participants from elsewhere, sending out its own groups, and hosting intra-urban processions. The processions reached Lucca on 9 August 1399, and continued on in some form for the next five or so months.

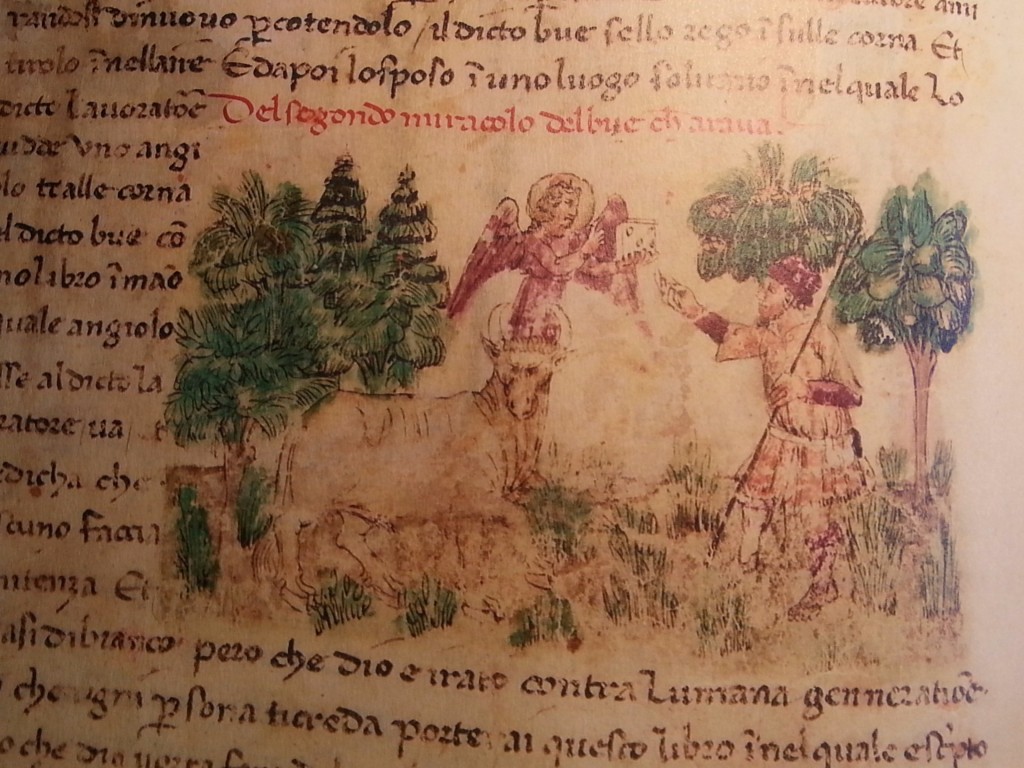

One way that Lucca is excpetional is the source material that we have for the Bianchi. In addition to municipal documents that explicitly mention the Bianchi, we have a beautifully illustrated chronicle by Giovanni Sercambi. Born and bred in Lucca, Sercambi’s chronicle starts in the twelfth century and dedicates around forty chapters to the Bianchi. This is a significant chunk of space, as most events are dealt with in just a single chapter.

Origin Narratives

As I’ve mentioned, plague was the key driving force for those joining the processions. This was a very real threat: plague was occurring roughly once a decade in Italy after the Black Death. This threat was communicated through up to three origin narratives, two of which are offered in Sercambi’s manuscript. The first, the most widely diffused is called the tre pani story, or story of the tree loaves. This is also present in other textual sources, and as frescoes on church walls in Umbria and Lazio. I have translated Sercambi’s version, and you can find other versions, as well as the images elsewhere on the blog.

The Lucca sources are the best we have for this narrative as Sercambi tells the story in both prose and as a lauda (song of praise), and each is richly illustrated, making a total of fifteen images. Other sources tell the story too, with slightly shorter versions in chronicles from Pistoia and Città di Castello, as well as frescoes in Umbria and Lazio, and various other laude. Sercambi’s source provides a helpful counterpoint to these other sources, filling in gaps, but also showing regional variation with details such as the type of bread mentioned.

Sercambi also sets out the expected practices for those participating in the devotions at the origin story stage: wearing white, fasting, praying and spreading the message of the devotions. These map onto other eyewitness accounts, but are less detailed than the Pistoia chronicle written by Dominici, which adds wearing a red cross, going barefoot, and the importance of peacemaking. Sercambi does mention Bianchi participants doing these things later on, just not as instructions in the origin narratives. This kind of variation just sets the scene for how different towns fulfulled and understood the divine instructions in different ways, such as placing the red cross on the shoulder for men and the head for women in Tuscany, but everyone wore it on both their shoulder and head in Lazio and Umbria.

The Bianchi at Lucca

Bianchi from elsewhere started arriving in Lucca on 9 August 1399, and were welcomed in. The townspeope started going to confession and communion to prepare to leave on their own processions. However, the town council decided that no-one would be allowed to leave Lucca, and closed the town gates. Before they had managed to do this, some eager Bianchi had managed to “escape” and travelled several kilometres to nearby Lunata. They could not be convinced to return, and so were allowed to conitnue on their journey,

Understandably, those left behind were quite cross, as they had not been allowed to participate in the plague-prevention processions. The authorities were faced with a conundrum: they had to mollify those left behind who had really wanted to leave. So, they tried a single day of processions within the town on 15 August, coinciding with the Assumption. This was not enough, and they soon had to organise a novena: nine days of processions within the walls of Lucca.

Processional Routes

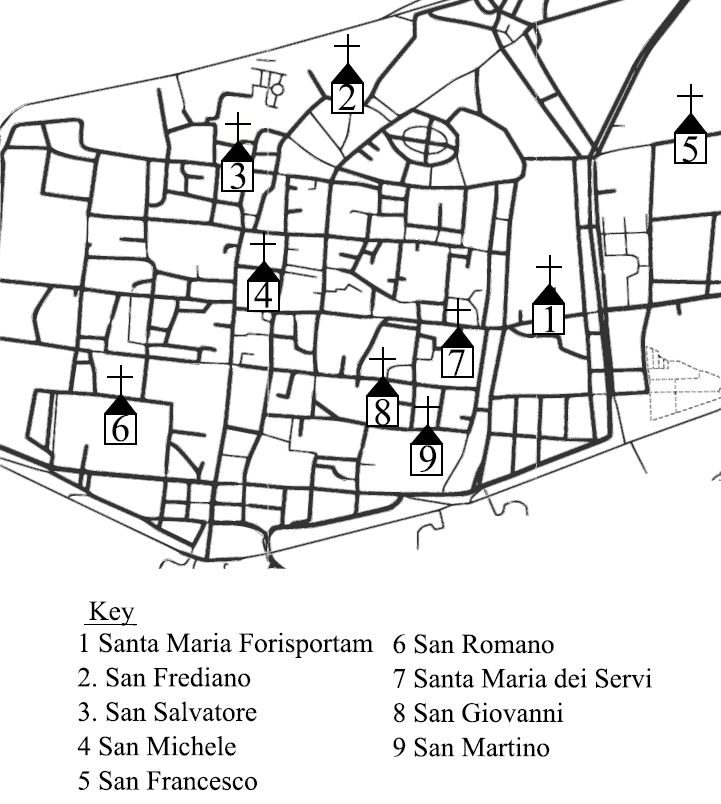

Each day, those remaining in Lucca would meet at a particular church, then would go on a procession to San Martino, the cathedral. The churches were Santa Maria Forisportam, San Frediano, San Salvatore, San Michele, San Francesco, San Romano, Santa Maria dei Servi, San Giovanni, and the ninth and final day was centred on San Martino itself. The churches were spread throughout the town, and each was quite large, with piazza space outside to accommodate the thousands of people reportedly joining in the processions. We don’t really know the routes followed, as none of the sources say how the processions got from point A to point B. However, I think it’s likely that all the routes would have been circuitous to allow for a good procession. The church of San Giovanni is on the corner of the cathedral piazza, and so would be a very short procession if they didn’t take a lengthier route on that day. Interestingly, in Pistoia, the churches selected for the intra-urban processions are more equidistant from the cathedral, so they didn’t encounter this problem. The Padua source written by Giovanni da Ravenna offers more precision on the routes taken, describing secular landmarks — this is one instance where Sercambi is outdone in terms of detail.

Eventually, itinerant participants were allowed to leave Lucca and there were two more groups which followed the first. One of these groups visited Castelfranco, San Miniato, Vicopisano, Calci, Cigoli, Vorno, Vico, Bu(i)ti, Badia di Guamo and Ponte(c)to. Taken place by place, this route involves lots of criss crossing and going back on itself, but does achieve roughly 25km between each town. This is similar to the distances covered by other itinerant Bianchi processions, such as those leaving Florence.

There was a significant degree of oversight both for the itinerant and the intra-urban processions to make sure they went smoothly. Luccehese authortiies provided food and drink, specifically bread wine and cheese. In Pistoia, this was supplemented with fruit, but in Florence there was a lack of generosity, so wealthy individuals had to chip in as well. Lucca sent wine and bread to participants on the road, as did Pistoia, to make sure they didn’t go hungry or thirsty. This meant that the towns had to know where the participants were each day, so that there was oversight over the routes.

Self-flagellation

The detail of the Lucca sources means we can be very nuanced in our understanding of how the Bianchi engaged with self-flagellation. The movement as a whole was not flagellant, as it wasn’t something that was expected from everyone. It was more that if you wanted to self-flagellate as it was already part of your devotional practice, you could be accommodated. There were three ways of participating in self-flagellation:

- Full self-flagellation with a whip on bare skin. We see this in Sercambi’s manuscript in the images accompanying many of the laude. Bianchi participants can be seen kneeling and whipping themselves through their backless robes and drawing blood. Crucially also this is done in front of devotional images, to provide a clear focus for those engaging in the practice.

- Carrying a whip and using it symbolically. All self-flagellation is symbolic of the suffering of Christ, but what I mean here is that the people carrying whips like this would not whip themselves to break their skin, but would do it over their clothes in a more symbolic fashion.

- Not flagellating at all. There are some people who just aren’t holding whips. This is often because they’re carrying candles too, so using a whip at the same time would be quite tricky.

There are some sources which suggest that everyone was flagellating willy-nilly, like the Pratese Datini, who carried a whip and reported people using them. However, thanks to the nuance in Sercambi, we can likely understand this as using the whip over clothing rather than breaking the skin. This lines up with another source from Florence, the poet Sacchetti who literally states that people were whipping themselves over their clothes. So, the Lucchese sources help us to understand that the Bianchi as a whole were not flagellant in the same way as previous revivals like in 1260, but that those who wanted to self-flagellate were free to do so within ritual contexts.

Legacy

If we look at Italy as a whole, it is easy to say that the Bianchi left no legacy. It’s at the local level where we can see traces though, and indeed in some cases traditions that still continue to this day. In Tuscany, I have identified a pattern of crucifixes and confraternities. Lucca has both. The confraternity of San Paolo was renamed to the Compagnia del Santissimo Crocifisso dei Bianchi and kept a miraculous Bianchi crucifix. They got new premises in 1500 and Giovanni Maracci painted a copper casing for the crucifix in the 1680s. The confraternitiy was still going in the early 1900s, albeit as a catechesis school, and finally dissolved in the 1970s.

This is very similar to other Tuscan examples. In Pistoia, a chapel was erected to house a Bianchi crucifix, and the confraternity of the Scalzati was founded, endorsed by the bishop Andrea Franchi. Borgo a Buggiano, near Lucca, also houses a Bianchi crucifix in the church now known as the Santuario del Santissimo Crocifisso, where an annual feast day was established and is still celebrated. A crucifix in Prato was similarly enshrined, with a special chapel created in the church of San Bartolomeo del Carmine. Numerous crucifixes survive in Florence, such as at San Michele Visdomini and Santa Lucia sul Prato. The history of Bianchi confraternities in Florence is somewhat complex, as many were retrospectively tied to the devotions in a moment of political division in the commune a century later. Nevertheless, these examples highlight this Tuscan pattern of commemoration in confraternities and crucifixes. This contrasts with a different legacy in Lazio and Umbria of frescoes, such as those discussed above at Terni and Vallo di Nera. Here again, the Lucchese evidence provides an important piece of the puzzle for dissecting the legacy of the Bianchi, underscoring the local attempts to commemorate the movement in the face of a lack of a more general commemoration across the spread of the devotions.

Conclusion

While short-lived, the Bianchi devotions made a significant impression on Lucca. The town was used as a sacred space by the participants and the Lucchese authorities intervened to provide material support, as well as organising the way that the processions functioned. After a shaky start, the Bianchi processions enjoyed significant support at Lucca. The Bianchi are given abundant space in Lucchese source materials, which achieves a rich picture of the devotions. However, it is only when we put these in combination with other sources, both in Tuscany and further afield, that we can understand what elements were specific to Lucca, and which elements were shared across the Bianchi devotions more broadly. The sources for the Bianchi at Lucca are therefore an important testimony to the movement, allowing us to deepen both local and comparative insights into the way the processions unfolded in 1399.